The complexities of DNA ethnicity estimations

Every month there’s been a helpful column in Family Tree magazine about using DNA to help discover more about your Ancestors. This month’s DNA Workshop has a great case study explaining how the various testing companies calculate ethnicity differently. I have thought that it is unfortunate that the DNA test’s most significant selling point is ethnicity because there are a variety of reasons why they could be inaccurate or vary from company to company. A company’s ethnicity result is only going to be as accurate as their panels. Ancestry, for example, skews more toward US and UK customers, so their source data will follow migration patterns relevant to their base customers. Also, it’s not uncommon to see your ethnicity results change over time as a testing company updates their science. Over on MyHeritage, you can see more of a European mix of DNA matches, and I do happen to know that their customers can skew more broadly into other countries because the resources they have available are more useful to those customers.

The March issue of Family Tree Magazine has some useful content for people interested in using DNA for their family history research.

Looking at my results on Ancestry, I don’t find them all that surprising. My mom’s side is still a bit of an unknown to me, but as she does come from Germany herself, it’s not a surprise that Europe features highly on my results. My dad’s side is 50% Kentucky (Colonial US), 37.5% Germany/Prussia (probably Eastern European skewed), and 12.5% Canadian (possibly via Scotland). So again, the United Kingdom (English) for the Kentucky side and Scotland via Canada migrations make sense to me here. Also, I have been able to trace a Kentucky line to Norway as well, so the Scandinavian connection also matches my research. France and Baltic estimations are where this might deviate the most from other services, but I don’t find them completely surprising. I haven’t found any evidence of these in my family, though, and the low numbers make me think they could be outliers. From this, I certainly wouldn’t go out and declare that I’m French in origin because I don’t know, or I wouldn’t entirely trust the data.

My DNA estimation as it appears in Ancestry.com on March 2020

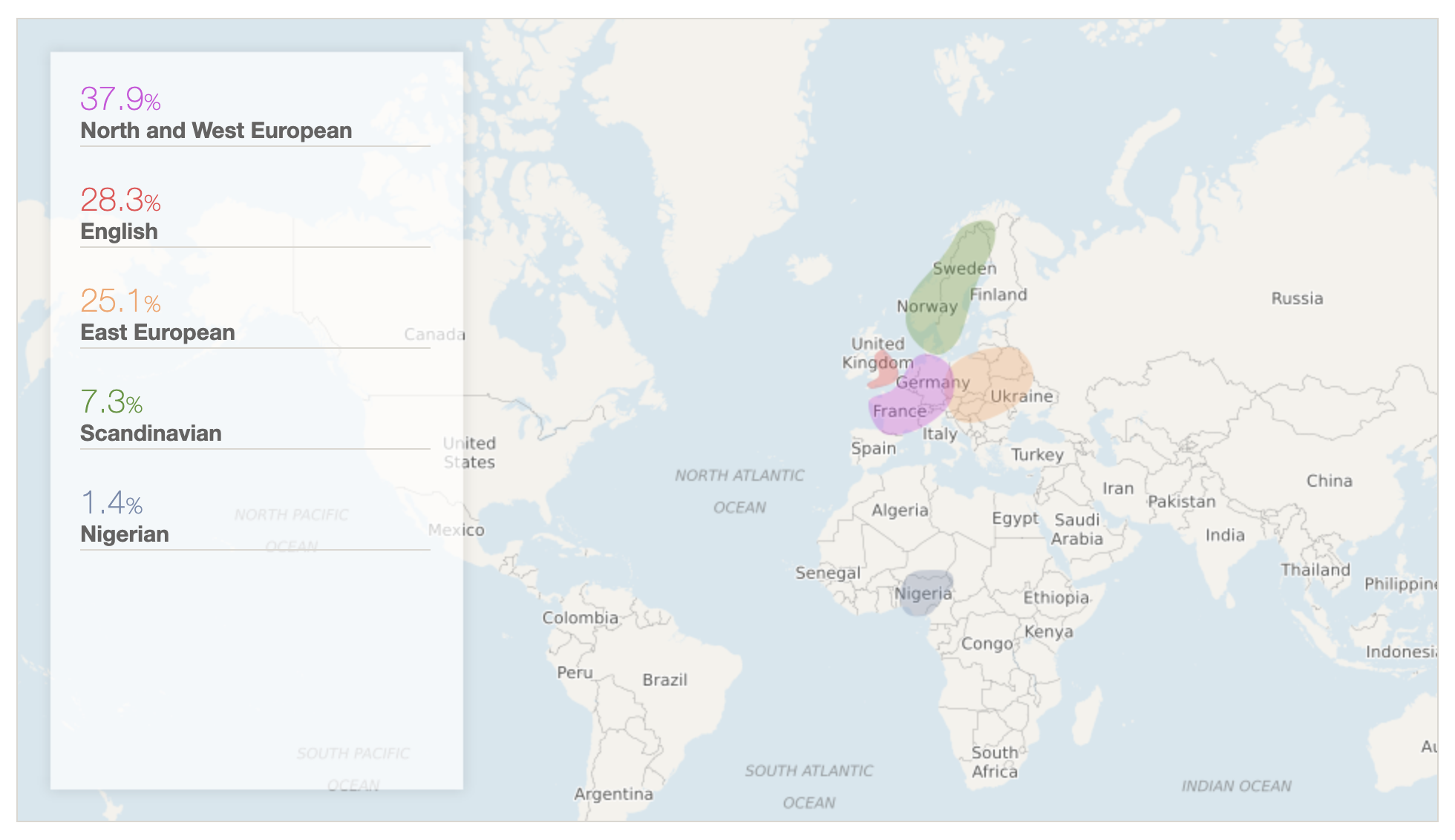

Comparing that to the MyHeritage results, they’re similar, but not the same. First of all, the Nigerian result is a bit of a surprise, but the size is so small, I would be willing to treat that as an outlier anyway. One of the more practical differences between testing companies is, of course, that DNA doesn’t know borders, and also borders as we know them today change over time. Because of this, it’s interesting to see how each company treats the exercise of labelling regions. Also, where those regions intersect as borders change over time is difficult to plot in a meaningful way to a customer (Ancestry does get credit for trying, but this can’t possibly be an exact science). What I do find particularly interesting about the MyHeritage results compared to the Ancestry ones is that MyHeritage specifically calls out English ancestry. Still, not Scottish, which I do know exists, so they’ve differentiated these places as separate regions, where I expect the borders to be more fluid. Then looking at Ancestry’s numbers again, they split “Germanic Europe” away from “East European”, but many of my “Germanic” ancestors were from the area that Ancestry has labelled “East European”.

My DNA estimation as it appears on MyHeritage.com as of March 2020

An excellent example of border and culture fluidity would be with my Prussian ancestors. Geographically, some would have been in what is known as Germany today, and others would be in what is Poland, however, all of them were German-speaking. These border changes are why researching your early German ancestors can be difficult, not exclusively because the availability of documentation today varies based on where they were born. Still, also culturally, I would never think of the ones that came from what is now Poland to be Polish because the culture they handed down to me through my ancestors was very much German. Even on census records in the US, these particular Eastern European ancestors would have either self-labelled as Prussian or German during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Ancestry defines this region as Eastern Europe and Russia with the origins primarily located in: Austria, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine; however all of my relatives from this region were probably German speaking.

I take these results with a pinch of salt. My research with DNA almost always focuses on my DNA matches, but the ethnicity results are not entirely useless in focused genealogical research. Where they have been useful for me is how migrations compare specifically with my match list. From these comparisons, I might be able to pick up clues to help me pinpoint a possible link to unknown matches, especially if those matches do not have trees attached to their match profiles. I would, however, say that if your only reason for getting a DNA test is to find out if you have Viking heritage, then your money might be better spent elsewhere. I just logged on to Ancestry ethnicity results for the first time in a while, and they had yet another update to their results with new science. Just because you tested with Viking heritage when you initially joined, doesn’t always mean you’ll still be a Viking the next time you log in! This science is frequently changing, though, and the accuracy will get better over time. However, for right now for it to be of use to mostly genealogical research, we still have to use it as a reasonable assumption rather than hard science.